The amazing Canadian Jewish woman behind the poppy on your jacket

Chances are, if you’re Canadian and it’s early November, there’s a red poppy on your Fall jacket. You probably already know that the poppies are sold by the Royal Canadian Legion in support of veterans, and that their use as a symbol of remembrance was inspired by Canadian poet John MacRae’s work In Flanders Fields.

But did you know that the origin of that poppy on your lapel - and of the Royal Canadian Legion itself – is bound up in the story of an astounding Canadian Jewish woman named Lillian Freiman?

Lillian Freiman

In 1915, Lillian Freiman installed 30 sewing machines in her home, and brought together a group of Jewish women to make sheets, blankets, clothes and, later, hospital gowns, as part of a Red Cross knitting and sewing club. The pattern for those gowns was adopted by the American Red Cross, and Lillian’s sewing group went on to become a chapter of the Daughters of the Empire. At that time, Lillian would have been 30 years old, with three young children at home.

In 1917, she had helped form the Ottawa chapter of the Great War Veterans’ Association of Canada, using her home as the headquarters. The GWVA became the Canadian Legion, and later, the Royal Canadian Legion. By 1919, it was the largest veterans’ organization in Canada.

In 1920, in France, inspired by John McRae’s poem In Flanders Fields, a Madame Guerin started a campaign where war widows and orphans would make and sell poppies to support veterans and their families.

An original Vetcraft poppy.

In 1921, Lillian Freiman brought the idea to Canada, organizing some women to make cloth poppies in her home and selling them in support of veterans. November 11, 1921 was Canada’s first Poppy Day, and Lillian was chair of that campaign for the rest of her life.

That same year, Lillian Freiman helped to form Vetcraft, a business that employed veterans in making furniture and toys so they could support themselves, and in 1923, Vetcraft took over the job of making and selling poppies as an additional source of funds.

More that just veterans

It would be a mistake to think that Lillian Freiman was only concerned with soldiers and veterans, though. As a teen she was involved with Ottawa’s Children’s Aid Society and the Hebrew Benevolent Society, laying the foundation for her lifetime of giving.

Lillian co-ordinated the response to the pandemic of 1918, organizing 1500 volunteers to keep three temporary hospitals in Ottawa equipped with the supplies they needed, and working with Ottawa’s chief medical officer to share updates and information.

Jewish causes

Freiman’s passion for service extended to Jewish causes as well. She was particularly concerned with the welfare of Jewish people in Russia, Ukraine, and eastern Poland after the First World War. Canadian policy at the time severely limited the number of Jews allowed to immigrate to Canada. Lillian and her husband, a successful businessman, had some influence with the leaders of the day. She used that influence to pressure the Immigration department to consider individual cases rather than having a blanket policy. Ultimately, she was able to bring 150 orphans to Canada, one of whom she adopted. At around the same time, she helped to prevent the deportation of hundreds of newly landed Jews.

Also around that time, she undertook a nation-wide fundraising tour for the Helping Hand Fund of Hadassah, raising what was then the unheard-of sum of $200,000, to support refugees.

Lillian Freiman and her husband were Zionists, like many Canadian Jews of the 1920’s and ‘30’s. Having been part of the movement to bring Hadassah to Canada from the United States, she pressed Hadassah to affiliate with its British counterpart. She served as the Dominion president of Canadian Hadassah-WIZO from 1919 until her death in 1940. While she was very ill and near death, she headed the Youth Aliyah Appeal from her sick bed, raising $18,000 to rescue Jewish children in Europe and resettle them in Palestine.

Recognition

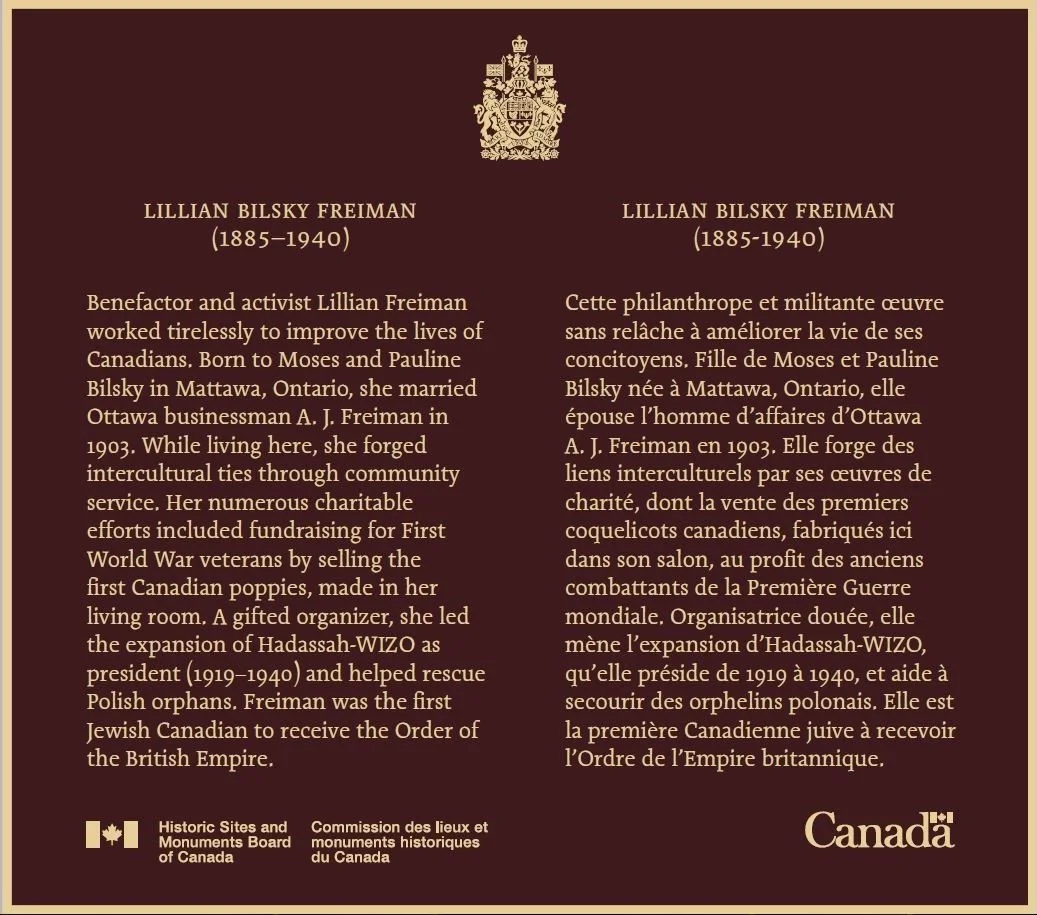

While Lillian Freiman’s story may not be widely known, she has been well recognized as an extraordinary woman. The Royal Canadian Legion made her an honorary member, in 1933, the first woman to be so honoured . In 1934 King George V made her the first Canadian Jew to receive an Order of the British Empire, and the following year, she was awarded the King George V Silver Jubilee Medal. She was named a National Historic Person by the Government of Canada in 2018, with a plaque in front of her former home in Ottawa (now the Canadian Army’s Officer’s Mess) marking her efforts at forging “intercultural ties through community service”.

Death

From the Canadian Heroes Comic Book series, published 1944.

Lillian Freiman died young, at the age of 55. The Dictionary of Canadian Biography describes what followed.

Lillian Freiman’s body lay at rest first in Montreal and then at her Ottawa home. Government departments allowed Jewish employees to take time off from work to attend the funeral, held at the King Edward Avenue Synagogue. All stores operated by Jews closed. A solemn procession of mourners made its way from the Freimans’ home to the synagogue, where those in attendance for the service included Prime Minister King, Ottawa mayor John Edward Stanley Lewis, Rabbi Maurice L. Perlsweig, representing the World Jewish Congress, and Samuel Bronfman, president of the Canadian Jewish Congress …. Perlsweig expressed the feelings of many when he declared that “the news of her passing will come as a personal grief to the multitudes of Zionist workers throughout the world whose affection and confidence she had won by her dedicated and selfless devotion.” Unprecedented in the tradition of Hebrew burial service, a wreath of poppies covered the lower half of the casket.

Read more about this remarkable woman:

The Canadian Encyclopedia: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/lillian-freiman

Jewis Women’s Archive: https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/freiman-lillian

Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lillian_Bilsky_Freiman

Canadian Dictionary of Biography: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bilsky_lillian_16E.html